Gherkin: Difference between revisions

| Line 515: | Line 515: | ||

= Cucumber reference = | = Cucumber reference = | ||

[https://cucumber.io/docs/gherkin/reference/ Cucumber reference] | [https://cucumber.io/docs/gherkin/reference/ Cucumber reference] | ||

Gherkin uses a set of special keywords to give structure and meaning to executable specifications. Each keyword is translated to many spoken languages; in this reference we’ll use English. | |||

Most lines in a Gherkin document start with one of the keywords. | |||

Comments are only permitted at the start of a new line, anywhere in the feature file. They begin with zero or more spaces, followed by a hash sign (#) and some text. | |||

Block comments are currently not supported by Gherkin. | |||

Either spaces or tabs may be used for indentation. The recommended indentation level is two spaces. Here is an example: | |||

Feature: Guess the word | |||

# The first example has two steps | |||

Scenario: Maker starts a game | |||

When the Maker starts a game | |||

Then the Maker waits for a Breaker to join | |||

# The second example has three steps | |||

Scenario: Breaker joins a game | |||

Given the Maker has started a game with the word "silky" | |||

When the Breaker joins the Maker's game | |||

Then the Breaker must guess a word with 5 characters | |||

The trailing portion (after the keyword) of each step is matched to a code block, called a step definition. | |||

Keywords | |||

Each line that isn’t a blank line has to start with a Gherkin keyword, followed by any text you like. The only exceptions are the feature and scenario descriptions. | |||

The primary keywords are: | |||

Feature | |||

Rule (as of Gherkin 6) | |||

Example (or Scenario) | |||

Given, When, Then, And, But for steps (or *) | |||

Background | |||

Scenario Outline (or Scenario Template) | |||

Examples | |||

There are a few secondary keywords as well: | |||

""" (Doc Strings) | |||

| (Data Tables) | |||

@ (Tags) | |||

# (Comments) | |||

Localisation | |||

Gherkin is localised for many spoken languages; each has their own localised equivalent of these keywords. | |||

Feature | |||

The purpose of the Feature keyword is to provide a high-level description of a software feature, and to group related scenarios. | |||

The first primary keyword in a Gherkin document must always be Feature, followed by a : and a short text that describes the feature. | |||

You can add free-form text underneath Feature to add more description. | |||

These description lines are ignored by Cucumber at runtime, but are available for reporting (They are included by default in html reports). | |||

Feature: Guess the word | |||

The word guess game is a turn-based game for two players. | |||

The Maker makes a word for the Breaker to guess. The game | |||

is over when the Breaker guesses the Maker's word. | |||

Example: Maker starts a game | |||

The name and the optional description have no special meaning to Cucumber. Their purpose is to provide a place for you to document important aspects of the feature, such as a brief explanation and a list of business rules (general acceptance criteria). | |||

The free format description for Feature ends when you start a line with the keyword Background, Rule, Example or Scenario Outline (or their alias keywords). | |||

You can place tags above Feature to group related features, independent of your file and directory structure. | |||

Descriptions | |||

Free-form descriptions (as described above for Feature) can also be placed underneath Example/Scenario, Background, Scenario Outline and Rule. | |||

You can write anything you like, as long as no line starts with a keyword. | |||

Rule | |||

The (optional) Rule keyword has been part of Gherkin since v6. | |||

Cucumber Support for Rule | |||

Not all Cucumber implementations have finished implementing support for the Rule keyword - see this issue for the latest status. | |||

The purpose of the Rule keyword is to represent one business rule that should be implemented. It provides additional information for a feature. A Rule is used to group together several scenarios that belong to this business rule. A Rule should contain one or more scenarios that illustrate the particular rule. | |||

For example: | |||

# -- FILE: features/gherkin.rule_example.feature | |||

Feature: Highlander | |||

Rule: There can be only One | |||

Example: Only One -- More than one alive | |||

Given there are 3 ninjas | |||

And there are more than one ninja alive | |||

When 2 ninjas meet, they will fight | |||

Then one ninja dies (but not me) | |||

And there is one ninja less alive | |||

Example: Only One -- One alive | |||

Given there is only 1 ninja alive | |||

Then he (or she) will live forever ;-) | |||

Rule: There can be Two (in some cases) | |||

Example: Two -- Dead and Reborn as Phoenix | |||

... | |||

Example | |||

This is a concrete example that illustrates a business rule. It consists of a list of steps. | |||

The keyword Scenario is a synonym of the keyword Example. | |||

You can have as many steps as you like, but we recommend you keep the number at 3-5 per example. Having too many steps in an example, will cause it to lose it’s expressive power as specification and documentation. | |||

In addition to being a specification and documentation, an example is also a test. As a whole, your examples are an executable specification of the system. | |||

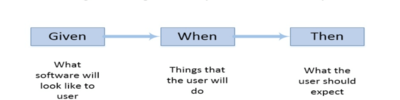

Examples follow this same pattern: | |||

Describe an initial context (Given steps) | |||

Describe an event (When steps) | |||

Describe an expected outcome (Then steps) | |||

Steps | |||

Each step starts with Given, When, Then, And, or But. | |||

Cucumber executes each step in a scenario one at a time, in the sequence you’ve written them in. When Cucumber tries to execute a step, it looks for a matching step definition to execute. | |||

Keywords are not taken into account when looking for a step definition. This means you cannot have a Given, When, Then, And or But step with the same text as another step. | |||

Cucumber considers the following steps duplicates: | |||

Given there is money in my account | |||

Then there is money in my account | |||

This might seem like a limitation, but it forces you to come up with a less ambiguous, more clear domain language: | |||

Given my account has a balance of £430 | |||

Then my account should have a balance of £430 | |||

Given | |||

Given steps are used to describe the initial context of the system - the scene of the scenario. It is typically something that happened in the past. | |||

When Cucumber executes a Given step, it will configure the system to be in a well-defined state, such as creating and configuring objects or adding data to a test database. | |||

The purpose of Given steps is to put the system in a known state before the user (or external system) starts interacting with the system (in the When steps). Avoid talking about user interaction in Given’s. If you were creating use cases, Given’s would be your preconditions. | |||

It’s okay to have several Given steps (use And or But for number 2 and upwards to make it more readable). | |||

Examples: | |||

Mickey and Minnie have started a game | |||

I am logged in | |||

Joe has a balance of £42 | |||

When | |||

When steps are used to describe an event, or an action. This can be a person interacting with the system, or it can be an event triggered by another system. | |||

It’s strongly recommended you only have a single When step per Scenario. If you feel compelled to add more, it’s usually a sign that you should split the scenario up into multiple scenarios. | |||

Examples: | |||

Guess a word | |||

Invite a friend | |||

Withdraw money | |||

Imagine it's 1922 | |||

Most software does something people could do manually (just not as efficiently). | |||

Try hard to come up with examples that don’t make any assumptions about technology or user interface. Imagine it’s 1922, when there were no computers. | |||

Implementation details should be hidden in the step definitions. | |||

Then | |||

Then steps are used to describe an expected outcome, or result. | |||

The step definition of a Then step should use an assertion to compare the actual outcome (what the system actually does) to the expected outcome (what the step says the system is supposed to do). | |||

An outcome should be on an observable output. That is, something that comes out of the system (report, user interface, message), and not a behaviour deeply buried inside the system (like a record in a database). | |||

Examples: | |||

See that the guessed word was wrong | |||

Receive an invitation | |||

Card should be swallowed | |||

While it might be tempting to implement Then steps to look in the database - resist that temptation! | |||

You should only verify an outcome that is observable for the user (or external system), and changes to a database are usually not. | |||

And, But | |||

If you have successive Given’s, When’s, or Then’s, you could write: | |||

Example: Multiple Givens | |||

Given one thing | |||

Given another thing | |||

Given yet another thing | |||

When I open my eyes | |||

Then I should see something | |||

Then I shouldn't see something else | |||

Or, you could make the example more fluidly structured by replacing the successive Given’s, When’s, or Then’s with And’s and But’s: | |||

Example: Multiple Givens | |||

Given one thing | |||

And another thing | |||

And yet another thing | |||

When I open my eyes | |||

Then I should see something | |||

But I shouldn't see something else | |||

* | |||

Gherkin also supports using an asterisk (*) in place of any of the normal step keywords. This can be helpful when you have some steps that are effectively a list of things, so you can express it more like bullet points where otherwise the natural language of And etc might not read so elegantly. | |||

For example: | |||

Scenario: All done | |||

Given I am out shopping | |||

And I have eggs | |||

And I have milk | |||

And I have butter | |||

When I check my list | |||

Then I don't need anything | |||

Could be expressed as: | |||

Scenario: All done | |||

Given I am out shopping | |||

* I have eggs | |||

* I have milk | |||

* I have butter | |||

When I check my list | |||

Then I don't need anything | |||

Background | |||

Occasionally you’ll find yourself repeating the same Given steps in all of the scenarios in a Feature. | |||

Since it is repeated in every scenario, this is an indication that those steps are not essential to describe the scenarios; they are incidental details. You can literally move such Given steps to the background, by grouping them under a Background section. | |||

A Background allows you to add some context to the scenarios that follow it. It can contain one or more Given steps, which are run before each scenario, but after any Before hooks. | |||

A Background is placed before the first Scenario/Example, at the same level of indentation. | |||

For example: | |||

Feature: Multiple site support | |||

Only blog owners can post to a blog, except administrators, | |||

who can post to all blogs. | |||

Background: | |||

Given a global administrator named "Greg" | |||

And a blog named "Greg's anti-tax rants" | |||

And a customer named "Dr. Bill" | |||

And a blog named "Expensive Therapy" owned by "Dr. Bill" | |||

Scenario: Dr. Bill posts to his own blog | |||

Given I am logged in as Dr. Bill | |||

When I try to post to "Expensive Therapy" | |||

Then I should see "Your article was published." | |||

Scenario: Dr. Bill tries to post to somebody else's blog, and fails | |||

Given I am logged in as Dr. Bill | |||

When I try to post to "Greg's anti-tax rants" | |||

Then I should see "Hey! That's not your blog!" | |||

Scenario: Greg posts to a client's blog | |||

Given I am logged in as Greg | |||

When I try to post to "Expensive Therapy" | |||

Then I should see "Your article was published." | |||

Background is also supported at the Rule level, for example: | |||

Feature: Overdue tasks | |||

Let users know when tasks are overdue, even when using other | |||

features of the app | |||

Rule: Users are notified about overdue tasks on first use of the day | |||

Background: | |||

Given I have overdue tasks | |||

Example: First use of the day | |||

Given I last used the app yesterday | |||

When I use the app | |||

Then I am notified about overdue tasks | |||

Example: Already used today | |||

Given I last used the app earlier today | |||

When I use the app | |||

Then I am not notified about overdue tasks | |||

... | |||

Use with caution | |||

Whilst usage of Background within Rule is currently supported, it’s not recommended, and may be removed in future versions of Gherkin. | |||

You can only have one set of Background steps per Feature or Rule. If you need different Background steps for different scenarios, consider breaking up your set of scenarios into more Rules or more Features. | |||

For a less explicit alternative to Background, check out conditional hooks. | |||

Tips for using Background | |||

Don’t use Background to set up complicated states, unless that state is actually something the client needs to know. | |||

For example, if the user and site names don’t matter to the client, use a higher-level step such as Given I am logged in as a site owner. | |||

Keep your Background section short. | |||

The client needs to actually remember this stuff when reading the scenarios. If the Background is more than 4 lines long, consider moving some of the irrelevant details into higher-level steps. | |||

Make your Background section vivid. | |||

Use colourful names, and try to tell a story. The human brain keeps track of stories much better than it keeps track of names like "User A", "User B", "Site 1", and so on. | |||

Keep your scenarios short, and don’t have too many. | |||

If the Background section has scrolled off the screen, the reader no longer has a full overview of what’s happening. Think about using higher-level steps, or splitting the *.feature file. | |||

Scenario Outline | |||

The Scenario Outline keyword can be used to run the same Scenario multiple times, with different combinations of values. | |||

The keyword Scenario Template is a synonym of the keyword Scenario Outline. | |||

Copying and pasting scenarios to use different values quickly becomes tedious and repetitive: | |||

Scenario: eat 5 out of 12 | |||

Given there are 12 cucumbers | |||

When I eat 5 cucumbers | |||

Then I should have 7 cucumbers | |||

Scenario: eat 5 out of 20 | |||

Given there are 20 cucumbers | |||

When I eat 5 cucumbers | |||

Then I should have 15 cucumbers | |||

We can collapse these two similar scenarios into a Scenario Outline. | |||

Scenario outlines allow us to more concisely express these scenarios through the use of a template with < >-delimited parameters: | |||

Scenario Outline: eating | |||

Given there are <start> cucumbers | |||

When I eat <eat> cucumbers | |||

Then I should have <left> cucumbers | |||

Examples: | |||

| start | eat | left | | |||

| 12 | 5 | 7 | | |||

| 20 | 5 | 15 | | |||

A Scenario Outline must contain an Examples (or Scenarios) section. Its steps are interpreted as a template which is never directly run. Instead, the Scenario Outline is run once for each row in the Examples section beneath it (not counting the first header row). | |||

The steps can use <> delimited parameters that reference headers in the examples table. Cucumber will replace these parameters with values from the table before it tries to match the step against a step definition. | |||

You can also use parameters in multiline step arguments. | |||

Step Arguments | |||

In some cases you might want to pass more data to a step than fits on a single line. For this purpose Gherkin has Doc Strings and Data Tables. | |||

Doc Strings | |||

Doc Strings are handy for passing a larger piece of text to a step definition. | |||

The text should be offset by delimiters consisting of three double-quote marks on lines of their own: | |||

Given a blog post named "Random" with Markdown body | |||

""" | |||

Some Title, Eh? | |||

=============== | |||

Here is the first paragraph of my blog post. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, | |||

consectetur adipiscing elit. | |||

""" | |||

In your step definition, there’s no need to find this text and match it in your pattern. It will automatically be passed as the last argument in the step definition. | |||

Indentation of the opening """ is unimportant, although common practice is two spaces in from the enclosing step. The indentation inside the triple quotes, however, is significant. Each line of the Doc String will be dedented according to the opening """. Indentation beyond the column of the opening “”” will therefore be preserved. | |||

Data Tables | |||

Data Tables are handy for passing a list of values to a step definition: | |||

Given the following users exist: | |||

| name | email | twitter | | |||

| Aslak | aslak@cucumber.io | @aslak_hellesoy | | |||

| Julien | julien@cucumber.io | @jbpros | | |||

| Matt | matt@cucumber.io | @mattwynne | | |||

Just like Doc Strings, Data Tables will be passed to the step definition as the last argument. | |||

Cucumber provides a rich API for manipulating tables from within step definitions. See the Data Table API reference reference for more details. | |||

Spoken Languages | |||

The language you choose for Gherkin should be the same language your users and domain experts use when they talk about the domain. Translating between two languages should be avoided. | |||

This is why Gherkin has been translated to over 70 languages . | |||

Here is a Gherkin scenario written in Norwegian: | |||

# language: no | |||

Funksjonalitet: Gjett et ord | |||

Eksempel: Ordmaker starter et spill | |||

Når Ordmaker starter et spill | |||

Så må Ordmaker vente på at Gjetter blir med | |||

Eksempel: Gjetter blir med | |||

Gitt at Ordmaker har startet et spill med ordet "bløtt" | |||

Når Gjetter blir med på Ordmakers spill | |||

Så må Gjetter gjette et ord på 5 bokstaver | |||

A # language: header on the first line of a feature file tells Cucumber what spoken language to use - for example # language: fr for French. If you omit this header, Cucumber will default to English (en). | |||

Some Cucumber implementations also let you set the default language in the configuration, so you don’t need to place the # language header in every file. | |||

Latest revision as of 09:23, 22 September 2020

Gherkin is a format to write user test stories with in a prefab format

Simple guide

https://www.guru99.com/gherkin-test-cucumber.html simple guide]

Why Gherkin?

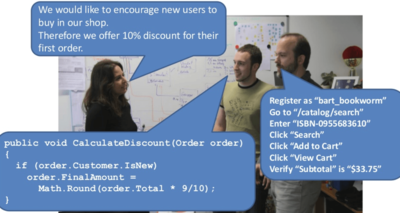

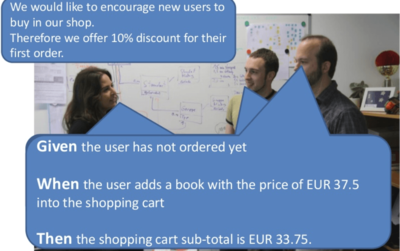

The need for Gherkin can be easily explained by following images

Before Gherkin

After Gherkin

Gherkin Syntax

Gherkin is line-oriented language just like YAML and Python. Each line called step and starts with keyword and end of the terminals with a stop. Tab or space are used for the indentation.

In this script, a comment can be added anywhere you want, but it should start with a # sign. It read each line after removing Ghrekin's keywords as given, when, then, etc.

Typical Gherkin steps look like:

Gherkin Scripts: connects the human concept of cause and effect to the software concept of input/process/output.

Gherkin Syntax:

Feature: Title of the Scenario Given [Preconditions or Initial Context] When [Event or Trigger] Then [Expected output]

A Gherkin document has an extension .feature and simply just a test file with a fancy extension. Cucumber reads Gherkin document and executes a test to validate that the software behaves as per the Gherkin cucumber syntax. Important Terms used in Gherkin

Feature Background Scenario Given When Then And But Scenario Outline Examples

The naming convention is used for feature name. However, there is no set rules in Cucumber about names.

Feature:

The file should have extension .feature and each feature file should have only one feature. The feature keyword being with the Feature: and after that add, a space and name of the feature will be written.

Scenario:

Each feature file may have multiple scenarios, and each scenario starts with Scenario: followed by scenario name.

Background:

Background keyword helps you to add some context to the scenario. It can contain some steps of the scenario, but the only difference is that it should be run before each scenario.

Given:

The use of Given keyword is to put the system in a familiar state before the user starts interacting with the system. However, you can omit writing user interactions in Given steps if Given in the "Precondition" step.

Syntax:

Given

Given - a test step that defines the 'context Given I am on "/."

When:

When the step is to define action performed by the user.

Syntax:

When

A When - a test step that defines the 'action' performed When I perform "Sign In."

Then:

The use of 'then' keyword is to see the outcome after the action in when step. However, you can only verify noticeable changes.

Syntax:

Then

Then - test step that defines the 'outcome.' Then I should see "Welcome Tom."

And & But

You may have multiple given when or Then.

Syntax:

But

A But - additional test step which defines the 'action' 'outcome.' But I should see "Welcome Tom."

And - additional test step that defines the 'action' performed And I write "EmailAddress" with "Tomjohn@gmail.com."

Given, When, Then, and, but are test steps. You can use them interchangeably. The interpreter doesn't display any error. However, they will surely not make any 'sense' when read.

Given The login page is opening When I input username, password and click the Login button Then I am on the Homepage

Gherkin Example

Feature: Login functionality of social networking site Facebook. Given: I am a facebook user. When: I enter username as username. And I enter the password as the password Then I should be redirected to the home page of facebook

The scenario mentioned above is of a feature called user login.

All the words written in bold are Gherkin keywords.

Gherkin will analyze each step written in the step definition file. Therefore, the steps are given in the feature file and the step definition file should match.

Example 2:

Feature: User Authentication Background: Given the user is already registered to the website Scenario: Given the user is on the login page When the user inputs the correct email address And the user inputs the correct password And the user clicks the Login button Then the user should be authenticated And the user should be redirected to their dashboard And the user should be presented with a success message

Best practices of using Gherkin

Each scenario should execute separately Every feature should able to be executed along Steps information should be shown independently Connect your Scenario's with your requirements Keep a complete track of what scenarios should be included in a requirement document Create modular and easy to understand steps Try to combine all your common scenarios

Advantage and Disadvantages of Gherkin

Gherkin is simple enough for non-programmers to understand Programmers can use it as a very solid base to start their tests It makes User Stories easier to digest Gherkin script can easily understand by business executives and developers Targets the business requirements A significant proportion of the functional specifications is written as user stories You don't need to be expert to understand the small Gherkin command set Gherkin links acceptance tests directly to automated tests Style of writing tests cases are easier to reuse code in other tests

Dis-Advantages

It requires a high level of business engagement and collaborations May not work well in all scenarios Poorly written tests can easily increase test-maintenance cost

Summary:

Gherkin is the format for cucumber specifications Gherkin is line-oriented language just like YAML and Python Gherkin Scripts connects the human concept of cause and effect to the software concept of input/process and output Feature, Background, Scenario, Given, When, Then, And But are importantly used in Gherkin In Gherkin cucumber, each scenario should execute separately The biggest advantage of Gherkin is simple enough for non-programmers to understand It may not work well in all type of scenarios

Behat guide

Writing Features - Gherkin Language

Behat is a tool to test the behavior of your application, described in special language called Gherkin. Gherkin is a Business Readable, Domain Specific Language created especially for behavior descriptions. It gives you the ability to remove logic details from behavior tests.

Gherkin serves two purposes: serving as your project’s documentation and automated tests. Behat also has a bonus feature: it talks back to you using real, human language telling you what code you should write.

If you’re still new to Behat, jump into the Quick Intro to Behat first, then return here to learn more about Gherkin. Gherkin Syntax

Like YAML or Python, Gherkin is a line-oriented language that uses indentation to define structure. Line endings terminate statements (called steps) and either spaces or tabs may be used for indentation. (We suggest you use spaces for portability.) Finally, most lines in Gherkin start with a special keyword:

Feature: Some terse yet descriptive text of what is desired

In order to realize a named business value As an explicit system actor I want to gain some beneficial outcome which furthers the goal

Scenario: Some determinable business situation

Given some precondition

And some other precondition

When some action by the actor

And some other action

And yet another action

Then some testable outcome is achieved

And something else we can check happens too

Scenario: A different situation

...

The parser divides the input into features, scenarios and steps. Let’s walk through the above example:

Feature: Some terse yet descriptive text of what is desired starts the feature and gives it a title. Learn more about features in the “Features” section. Behat does not parse the next 3 lines of text. (In order to... As an... I want to...). These lines simply provide context to the people reading your feature, and describe the business value derived from the inclusion of the feature in your software. Scenario: Some determinable business situation starts the scenario, and contains a description of the scenario. Learn more about scenarios in the “Scenarios” section. The next 7 lines are the scenario steps, each of which is matched to a regular expression defined elsewhere. Learn more about steps in the “Steps” section. Scenario: A different situation starts the next scenario, and so on.

When you’re executing the feature, the trailing portion of each step (after keywords like Given, And, When, etc) is matched to a regular expression, which executes a PHP callback function. You can read more about steps matching and execution in Defining Reusable Actions - Step Definitions. Features

Every *.feature file conventionally consists of a single feature. Lines starting with the keyword Feature: (or its localized equivalent) followed by three indented lines starts a feature. A feature usually contains a list of scenarios. You can write whatever you want up until the first scenario, which starts with Scenario: (or localized equivalent) on a new line. You can use tags to group features and scenarios together, independent of your file and directory structure.

Every scenario consists of a list of steps, which must start with one of the keywords Given, When, Then, But or And (or localized one). Behat treats them all the same, but you shouldn’t. Here is an example:

Feature: Serve coffee

In order to earn money Customers should be able to buy coffee at all times

Scenario: Buy last coffee Given there are 1 coffees left in the machine And I have deposited 1 dollar When I press the coffee button Then I should be served a coffee

In addition to basic scenarios, feature may contain scenario outlines and backgrounds. Scenarios

Scenario is one of the core Gherkin structures. Every scenario starts with the Scenario: keyword (or localized one), followed by an optional scenario title. Each feature can have one or more scenarios, and every scenario consists of one or more steps.

The following scenarios each have 3 steps:

Scenario: Wilson posts to his own blog

Given I am logged in as Wilson When I try to post to "Expensive Therapy" Then I should see "Your article was published."

Scenario: Wilson fails to post to somebody else's blog

Given I am logged in as Wilson When I try to post to "Greg's anti-tax rants" Then I should see "Hey! That's not your blog!"

Scenario: Greg posts to a client's blog

Given I am logged in as Greg When I try to post to "Expensive Therapy" Then I should see "Your article was published."

Scenario Outlines

Copying and pasting scenarios to use different values can quickly become tedious and repetitive:

Scenario: Eat 5 out of 12

Given there are 12 cucumbers When I eat 5 cucumbers Then I should have 7 cucumbers

Scenario: Eat 5 out of 20

Given there are 20 cucumbers When I eat 5 cucumbers Then I should have 15 cucumbers

Scenario Outlines allow us to more concisely express these examples through the use of a template with placeholders:

Scenario Outline: Eating

Given there are <start> cucumbers When I eat <eat> cucumbers Then I should have <left> cucumbers

Examples: | start | eat | left | | 12 | 5 | 7 | | 20 | 5 | 15 |

The Scenario outline steps provide a template which is never directly run. A Scenario Outline is run once for each row in the Examples section beneath it (not counting the first row of column headers).

The Scenario Outline uses placeholders, which are contained within < > in the Scenario Outline’s steps. For example:

Given <I'm a placeholder and I'm ok>

Think of a placeholder like a variable. It is replaced with a real value from the Examples: table row, where the text between the placeholder angle brackets matches that of the table column header. The value substituted for the placeholder changes with each subsequent run of the Scenario Outline, until the end of the Examples table is reached.

You can also use placeholders in Multiline Arguments.

Your step definitions will never have to match the placeholder text itself, but rather the values replacing the placeholder.

So when running the first row of our example:

Scenario Outline: controlling order

Given there are <start> cucumbers When I eat <eat> cucumbers Then I should have <left> cucumbers

Examples: | start | eat | left | | 12 | 5 | 7 |

The scenario that is actually run is:

Scenario Outline: controlling order

# <start> replaced with 12: Given there are 12 cucumbers # <eat> replaced with 5: When I eat 5 cucumbers # <left> replaced with 7: Then I should have 7 cucumbers

Backgrounds

Backgrounds allows you to add some context to all scenarios in a single feature. A Background is like an untitled scenario, containing a number of steps. The difference is when it is run: the background is run before each of your scenarios, but after your BeforeScenario hooks (Hooking into the Test Process - Hooks).

Feature: Multiple site support

Background: Given a global administrator named "Greg" And a blog named "Greg's anti-tax rants" And a customer named "Wilson" And a blog named "Expensive Therapy" owned by "Wilson"

Scenario: Wilson posts to his own blog Given I am logged in as Wilson When I try to post to "Expensive Therapy" Then I should see "Your article was published."

Scenario: Greg posts to a client's blog Given I am logged in as Greg When I try to post to "Expensive Therapy" Then I should see "Your article was published."

Steps

Features consist of steps, also known as Givens, Whens and Thens.

Behat doesn’t technically distinguish between these three kind of steps. However, we strongly recommend that you do! These words have been carefully selected for their purpose, and you should know what the purpose is to get into the BDD mindset.

Robert C. Martin has written a great post about BDD’s Given-When-Then concept where he thinks of them as a finite state machine. Givens

The purpose of Given steps is to put the system in a known state before the user (or external system) starts interacting with the system (in the When steps). Avoid talking about user interaction in givens. If you have worked with use cases, givens are your preconditions.

Two good examples of using Givens are:

To create records (model instances) or set up the database:

Given there are no users on site

Given the database is clean

Authenticate a user (An exception to the no-interaction recommendation. Things that “happened earlier” are ok):

Given I am logged in as "Everzet"

It’s ok to call into the layer “inside” the UI layer here (in symfony: talk to the models).

And for all the symfony users out there, we recommend using a Given step with a tables arguments to set up records instead of fixtures. This way you can read the scenario all in one place and make sense out of it without having to jump between files:

Given there are users:

| username | password | email | | everzet | 123456 | everzet@knplabs.com | | fabpot | 22@222 | fabpot@symfony.com |

Whens

The purpose of When steps is to describe the key action the user performs (or, using Robert C. Martin’s metaphor, the state transition).

Two good examples of Whens use are:

Interact with a web page (the Mink library gives you many web-friendly When steps out of the box):

When I am on "/some/page"

When I fill "username" with "everzet"

When I fill "password" with "123456"

When I press "login"

Interact with some CLI library (call commands and record output):

When I call "ls -la"

Thens

The purpose of Then steps is to observe outcomes. The observations should be related to the business value/benefit in your feature description. The observations should inspect the output of the system (a report, user interface, message, command output) and not something deeply buried inside it (that has no business value and is instead part of the implementation).

Verify that something related to the Given+When is (or is not) in the output Check that some external system has received the expected message (was an email with specific content successfully sent?)

When I call "echo hello" Then the output should be "hello"

While it might be tempting to implement Then steps to just look in the database – resist the temptation. You should only verify output that is observable by the user (or external system). Database data itself is only visible internally to your application, but is then finally exposed by the output of your system in a web browser, on the command-line or an email message. And, But

If you have several Given, When or Then steps you can write:

Scenario: Multiple Givens

Given one thing Given an other thing Given yet an other thing When I open my eyes Then I see something Then I don't see something else

Or you can use And or But steps, allowing your Scenario to read more fluently:

Scenario: Multiple Givens

Given one thing And an other thing And yet an other thing When I open my eyes Then I see something But I don't see something else

If you prefer, you can indent scenario steps in a more programmatic way, much in the same way your actual code is indented to provide visual context:

Scenario: Multiple Givens

Given one thing And an other thing And yet an other thing When I open my eyes Then I see something But I don't see something else

Behat interprets steps beginning with And or But exactly the same as all other steps. It doesn’t differ between them - you should! Multiline Arguments

The regular expression matching in steps lets you capture small strings from your steps and receive them in your step definitions. However, there are times when you want to pass a richer data structure from a step to a step definition.

This is what multiline step arguments are for. They are written on lines immediately following a step, and are passed to the step definition method as the last argument.

Multiline step arguments come in two flavours: tables or pystrings. Tables

Tables as arguments to steps are handy for specifying a larger data set - usually as input to a Given or as expected output from a Then.

Scenario:

Given the following people exist: | name | email | phone | | Aslak | aslak@email.com | 123 | | Joe | joe@email.com | 234 | | Bryan | bryan@email.org | 456 |

Don’t be confused with tables from scenario outlines - syntactically they are identical, but have a different purpose.

A matching definition for this step looks like this:

/**

* @Given /the following people exist:/ */

public function thePeopleExist(TableNode $table) {

$hash = $table->getHash();

foreach ($hash as $row) {

// $row['name'], $row['email'], $row['phone']

}

}

A table is injected into a definition as a TableNode object, from which you can get hash by columns (TableNode::getHash() method) or by rows (TableNode::getRowsHash()). PyStrings

Multiline Strings (also known as PyStrings) are handy for specifying a larger piece of text. This is done using the so-called PyString syntax. The text should be offset by delimiters consisting of three double-quote marks (""") on lines by themselves:

Scenario:

Given a blog post named "Random" with: """ Some Title, Eh? =============== Here is the first paragraph of my blog post. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. """

The inspiration for PyString comes from Python where """ is used to delineate docstrings, much in the way /* ... */ is used for multiline docblocks in PHP.

In your step definition, there’s no need to find this text and match it in your regular expression. The text will automatically be passed as the last argument into the step definition method. For example:

/**

* @Given /a blog post named "([^"]+)" with:/ */

public function blogPost($title, PyStringNode $markdown) {

$this->createPost($title, $markdown->getRaw());

}

PyStrings are stored in a PyStringNode instance, which you can simply convert to a string with (string) $pystring or $pystring->getRaw() as in the example above.

Indentation of the opening """ is not important, although common practice is two spaces in from the enclosing step. The indentation inside the triple quotes, however, is significant. Each line of the string passed to the step definition’s callback will be de-indented according to the opening """. Indentation beyond the column of the opening """ will therefore be preserved. Tags

Tags are a great way to organize your features and scenarios. Consider this example:

@billing Feature: Verify billing

@important Scenario: Missing product description

Scenario: Several products

A Scenario or Feature can have as many tags as you like, just separate them with spaces:

@billing @bicker @annoy Feature: Verify billing

If a tag exists on a Feature, Behat will assign that tag to all child Scenarios and Scenario Outlines too.

Cucumber reference

Gherkin uses a set of special keywords to give structure and meaning to executable specifications. Each keyword is translated to many spoken languages; in this reference we’ll use English.

Most lines in a Gherkin document start with one of the keywords.

Comments are only permitted at the start of a new line, anywhere in the feature file. They begin with zero or more spaces, followed by a hash sign (#) and some text.

Block comments are currently not supported by Gherkin.

Either spaces or tabs may be used for indentation. The recommended indentation level is two spaces. Here is an example:

Feature: Guess the word

# The first example has two steps Scenario: Maker starts a game When the Maker starts a game Then the Maker waits for a Breaker to join

# The second example has three steps Scenario: Breaker joins a game Given the Maker has started a game with the word "silky" When the Breaker joins the Maker's game Then the Breaker must guess a word with 5 characters

The trailing portion (after the keyword) of each step is matched to a code block, called a step definition. Keywords

Each line that isn’t a blank line has to start with a Gherkin keyword, followed by any text you like. The only exceptions are the feature and scenario descriptions.

The primary keywords are:

Feature Rule (as of Gherkin 6) Example (or Scenario) Given, When, Then, And, But for steps (or *) Background Scenario Outline (or Scenario Template) Examples

There are a few secondary keywords as well:

""" (Doc Strings) | (Data Tables) @ (Tags) # (Comments)

Localisation

Gherkin is localised for many spoken languages; each has their own localised equivalent of these keywords. Feature

The purpose of the Feature keyword is to provide a high-level description of a software feature, and to group related scenarios.

The first primary keyword in a Gherkin document must always be Feature, followed by a : and a short text that describes the feature.

You can add free-form text underneath Feature to add more description.

These description lines are ignored by Cucumber at runtime, but are available for reporting (They are included by default in html reports).

Feature: Guess the word

The word guess game is a turn-based game for two players. The Maker makes a word for the Breaker to guess. The game is over when the Breaker guesses the Maker's word.

Example: Maker starts a game

The name and the optional description have no special meaning to Cucumber. Their purpose is to provide a place for you to document important aspects of the feature, such as a brief explanation and a list of business rules (general acceptance criteria).

The free format description for Feature ends when you start a line with the keyword Background, Rule, Example or Scenario Outline (or their alias keywords).

You can place tags above Feature to group related features, independent of your file and directory structure. Descriptions

Free-form descriptions (as described above for Feature) can also be placed underneath Example/Scenario, Background, Scenario Outline and Rule.

You can write anything you like, as long as no line starts with a keyword. Rule

The (optional) Rule keyword has been part of Gherkin since v6.

Cucumber Support for Rule

Not all Cucumber implementations have finished implementing support for the Rule keyword - see this issue for the latest status.

The purpose of the Rule keyword is to represent one business rule that should be implemented. It provides additional information for a feature. A Rule is used to group together several scenarios that belong to this business rule. A Rule should contain one or more scenarios that illustrate the particular rule.

For example:

- -- FILE: features/gherkin.rule_example.feature

Feature: Highlander

Rule: There can be only One

Example: Only One -- More than one alive

Given there are 3 ninjas

And there are more than one ninja alive

When 2 ninjas meet, they will fight

Then one ninja dies (but not me)

And there is one ninja less alive

Example: Only One -- One alive

Given there is only 1 ninja alive

Then he (or she) will live forever ;-)

Rule: There can be Two (in some cases)

Example: Two -- Dead and Reborn as Phoenix

...

Example

This is a concrete example that illustrates a business rule. It consists of a list of steps.

The keyword Scenario is a synonym of the keyword Example.

You can have as many steps as you like, but we recommend you keep the number at 3-5 per example. Having too many steps in an example, will cause it to lose it’s expressive power as specification and documentation.

In addition to being a specification and documentation, an example is also a test. As a whole, your examples are an executable specification of the system.

Examples follow this same pattern:

Describe an initial context (Given steps) Describe an event (When steps) Describe an expected outcome (Then steps)

Steps

Each step starts with Given, When, Then, And, or But.

Cucumber executes each step in a scenario one at a time, in the sequence you’ve written them in. When Cucumber tries to execute a step, it looks for a matching step definition to execute.

Keywords are not taken into account when looking for a step definition. This means you cannot have a Given, When, Then, And or But step with the same text as another step.

Cucumber considers the following steps duplicates:

Given there is money in my account Then there is money in my account

This might seem like a limitation, but it forces you to come up with a less ambiguous, more clear domain language:

Given my account has a balance of £430 Then my account should have a balance of £430

Given

Given steps are used to describe the initial context of the system - the scene of the scenario. It is typically something that happened in the past.

When Cucumber executes a Given step, it will configure the system to be in a well-defined state, such as creating and configuring objects or adding data to a test database.

The purpose of Given steps is to put the system in a known state before the user (or external system) starts interacting with the system (in the When steps). Avoid talking about user interaction in Given’s. If you were creating use cases, Given’s would be your preconditions.

It’s okay to have several Given steps (use And or But for number 2 and upwards to make it more readable).

Examples:

Mickey and Minnie have started a game I am logged in Joe has a balance of £42

When

When steps are used to describe an event, or an action. This can be a person interacting with the system, or it can be an event triggered by another system.

It’s strongly recommended you only have a single When step per Scenario. If you feel compelled to add more, it’s usually a sign that you should split the scenario up into multiple scenarios.

Examples:

Guess a word Invite a friend Withdraw money

Imagine it's 1922

Most software does something people could do manually (just not as efficiently).

Try hard to come up with examples that don’t make any assumptions about technology or user interface. Imagine it’s 1922, when there were no computers.

Implementation details should be hidden in the step definitions. Then

Then steps are used to describe an expected outcome, or result.

The step definition of a Then step should use an assertion to compare the actual outcome (what the system actually does) to the expected outcome (what the step says the system is supposed to do).

An outcome should be on an observable output. That is, something that comes out of the system (report, user interface, message), and not a behaviour deeply buried inside the system (like a record in a database).

Examples:

See that the guessed word was wrong Receive an invitation Card should be swallowed

While it might be tempting to implement Then steps to look in the database - resist that temptation!

You should only verify an outcome that is observable for the user (or external system), and changes to a database are usually not. And, But

If you have successive Given’s, When’s, or Then’s, you could write:

Example: Multiple Givens

Given one thing Given another thing Given yet another thing When I open my eyes Then I should see something Then I shouldn't see something else

Or, you could make the example more fluidly structured by replacing the successive Given’s, When’s, or Then’s with And’s and But’s:

Example: Multiple Givens

Given one thing And another thing And yet another thing When I open my eyes Then I should see something But I shouldn't see something else

Gherkin also supports using an asterisk (*) in place of any of the normal step keywords. This can be helpful when you have some steps that are effectively a list of things, so you can express it more like bullet points where otherwise the natural language of And etc might not read so elegantly.

For example:

Scenario: All done

Given I am out shopping And I have eggs And I have milk And I have butter When I check my list Then I don't need anything

Could be expressed as:

Scenario: All done

Given I am out shopping * I have eggs * I have milk * I have butter When I check my list Then I don't need anything

Background

Occasionally you’ll find yourself repeating the same Given steps in all of the scenarios in a Feature.

Since it is repeated in every scenario, this is an indication that those steps are not essential to describe the scenarios; they are incidental details. You can literally move such Given steps to the background, by grouping them under a Background section.

A Background allows you to add some context to the scenarios that follow it. It can contain one or more Given steps, which are run before each scenario, but after any Before hooks.

A Background is placed before the first Scenario/Example, at the same level of indentation.

For example:

Feature: Multiple site support

Only blog owners can post to a blog, except administrators, who can post to all blogs.

Background: Given a global administrator named "Greg" And a blog named "Greg's anti-tax rants" And a customer named "Dr. Bill" And a blog named "Expensive Therapy" owned by "Dr. Bill"

Scenario: Dr. Bill posts to his own blog Given I am logged in as Dr. Bill When I try to post to "Expensive Therapy" Then I should see "Your article was published."

Scenario: Dr. Bill tries to post to somebody else's blog, and fails Given I am logged in as Dr. Bill When I try to post to "Greg's anti-tax rants" Then I should see "Hey! That's not your blog!"

Scenario: Greg posts to a client's blog Given I am logged in as Greg When I try to post to "Expensive Therapy" Then I should see "Your article was published."

Background is also supported at the Rule level, for example:

Feature: Overdue tasks

Let users know when tasks are overdue, even when using other features of the app

Rule: Users are notified about overdue tasks on first use of the day

Background:

Given I have overdue tasks

Example: First use of the day

Given I last used the app yesterday

When I use the app

Then I am notified about overdue tasks

Example: Already used today

Given I last used the app earlier today

When I use the app

Then I am not notified about overdue tasks

...

Use with caution

Whilst usage of Background within Rule is currently supported, it’s not recommended, and may be removed in future versions of Gherkin.

You can only have one set of Background steps per Feature or Rule. If you need different Background steps for different scenarios, consider breaking up your set of scenarios into more Rules or more Features.

For a less explicit alternative to Background, check out conditional hooks. Tips for using Background

Don’t use Background to set up complicated states, unless that state is actually something the client needs to know.

For example, if the user and site names don’t matter to the client, use a higher-level step such as Given I am logged in as a site owner.

Keep your Background section short.

The client needs to actually remember this stuff when reading the scenarios. If the Background is more than 4 lines long, consider moving some of the irrelevant details into higher-level steps.

Make your Background section vivid.

Use colourful names, and try to tell a story. The human brain keeps track of stories much better than it keeps track of names like "User A", "User B", "Site 1", and so on.

Keep your scenarios short, and don’t have too many.

If the Background section has scrolled off the screen, the reader no longer has a full overview of what’s happening. Think about using higher-level steps, or splitting the *.feature file.

Scenario Outline

The Scenario Outline keyword can be used to run the same Scenario multiple times, with different combinations of values.

The keyword Scenario Template is a synonym of the keyword Scenario Outline.

Copying and pasting scenarios to use different values quickly becomes tedious and repetitive:

Scenario: eat 5 out of 12

Given there are 12 cucumbers When I eat 5 cucumbers Then I should have 7 cucumbers

Scenario: eat 5 out of 20

Given there are 20 cucumbers When I eat 5 cucumbers Then I should have 15 cucumbers

We can collapse these two similar scenarios into a Scenario Outline.

Scenario outlines allow us to more concisely express these scenarios through the use of a template with < >-delimited parameters:

Scenario Outline: eating

Given there are <start> cucumbers When I eat <eat> cucumbers Then I should have <left> cucumbers

Examples: | start | eat | left | | 12 | 5 | 7 | | 20 | 5 | 15 |

A Scenario Outline must contain an Examples (or Scenarios) section. Its steps are interpreted as a template which is never directly run. Instead, the Scenario Outline is run once for each row in the Examples section beneath it (not counting the first header row).

The steps can use <> delimited parameters that reference headers in the examples table. Cucumber will replace these parameters with values from the table before it tries to match the step against a step definition.

You can also use parameters in multiline step arguments. Step Arguments

In some cases you might want to pass more data to a step than fits on a single line. For this purpose Gherkin has Doc Strings and Data Tables. Doc Strings

Doc Strings are handy for passing a larger piece of text to a step definition.

The text should be offset by delimiters consisting of three double-quote marks on lines of their own:

Given a blog post named "Random" with Markdown body

""" Some Title, Eh? =============== Here is the first paragraph of my blog post. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. """

In your step definition, there’s no need to find this text and match it in your pattern. It will automatically be passed as the last argument in the step definition.

Indentation of the opening """ is unimportant, although common practice is two spaces in from the enclosing step. The indentation inside the triple quotes, however, is significant. Each line of the Doc String will be dedented according to the opening """. Indentation beyond the column of the opening “”” will therefore be preserved. Data Tables

Data Tables are handy for passing a list of values to a step definition:

Given the following users exist:

| name | email | twitter | | Aslak | aslak@cucumber.io | @aslak_hellesoy | | Julien | julien@cucumber.io | @jbpros | | Matt | matt@cucumber.io | @mattwynne |

Just like Doc Strings, Data Tables will be passed to the step definition as the last argument.

Cucumber provides a rich API for manipulating tables from within step definitions. See the Data Table API reference reference for more details. Spoken Languages

The language you choose for Gherkin should be the same language your users and domain experts use when they talk about the domain. Translating between two languages should be avoided.

This is why Gherkin has been translated to over 70 languages .

Here is a Gherkin scenario written in Norwegian:

- language: no

Funksjonalitet: Gjett et ord

Eksempel: Ordmaker starter et spill Når Ordmaker starter et spill Så må Ordmaker vente på at Gjetter blir med

Eksempel: Gjetter blir med Gitt at Ordmaker har startet et spill med ordet "bløtt" Når Gjetter blir med på Ordmakers spill Så må Gjetter gjette et ord på 5 bokstaver

A # language: header on the first line of a feature file tells Cucumber what spoken language to use - for example # language: fr for French. If you omit this header, Cucumber will default to English (en).

Some Cucumber implementations also let you set the default language in the configuration, so you don’t need to place the # language header in every file.